Find out more about about the history behind Liberty’s Fire

1March 2, 2015 by Lydia Syson

‘What is the Commune, that sphinx so tantalizing to the bourgeois mind?’ (Marx:The Civil War in France)

Simply put, the Paris Commune was the radical municipal government elected to run the French capital in March 1871, immediately after the Franco-Prussian War and the Siege of Paris – not to be confused with the first French Revolution in 1789, or the July Revolution of 1830, or indeed the small uprising of 1832 featured in Les Miserables, or even the 1848 revolution which brought in the short-lived Second Republic. It lasted for 72 days, and historians have been debating exactly how to define it ever since.

When the Commune was put down by France’s national government, Paris burned for a week and thousands of Communards were slaughtered on the streets of the city. Thousands more were imprisoned, some to be executed, some exiled to New Caledonia. The Commune played a huge but now often forgotten part in shaping twentieth-century history, as it had a profound influence on both Marx and Lenin: Lenin supposedly danced in the snow when his revolution lasted longer than the Commune.

Here are some of the books, articles, films, museums and archives which shaped my thinking while I was writing Liberty’s Fire. Needless to say, this list is far from exhaustive, but I hope it will provide some good places to start finding out more. Do contact me with any further suggestions or recommendations. I’ve included translations where they exist, and many links to out-of-print editions available online, but some material is only in French. The material is divided into the following sections, though I’m afraid you’ll have to scroll down to find each one.

20th- and 21st-century general histories of the Commune and Franco-Prussian War

Women in the Commune

Contemporary (eye-witness) accounts

Photography & other visual sources

Music

Nineteenth-century Paris

Homosexuality in nineteenth-century Paris

Fiction

Museums and places in Paris

Useful online archives & bibliographies and other stuff

New material

**************************************************************************************

One book that doesn’t fit into any of these categories, but set the whole thing off for me: Angela John‘s War, Journalism and the Shaping of the Twentieth Century: The Life and Times of Henry W. Nevinson (2006).

One book that doesn’t fit into any of these categories, but set the whole thing off for me: Angela John‘s War, Journalism and the Shaping of the Twentieth Century: The Life and Times of Henry W. Nevinson (2006).

20th- and 21st-century general histories of the Commune and Franco-Prussian War

These two books were published too late to be very useful to Liberty’s Fire, but both are both fascinating and represent the latest research and thinking in English on the Commune, as well as being good examples of historians’ tendencies to focus on either ideas and their significance or events and lived experience (both approaches are of course useful):

Kristin Ross, Communal Luxury: the Political Imaginary of the Paris Commune, (Verso, 2015)

(The title is taken from Eugene Pottier artists’ manifesto, written in Paris in April 1871, a phrase which set out to ‘counteract and defy the abject “misérabilisme” of Versaillais depictions of Parisian life under the Commune’, p.64. By June, Pottier was writing the words for the International: ‘Arise, ye starvelings from your slumbers…’)

John Merriman, Massacre: The Life and Death of the Paris Commune of 1871, (Yale University press, 2014)

This was the book to which I returned most frequently:

Robert Tombs, The Paris Commune, 1871 (Pearson Educational, 1999)

. . .and I also relied a great deal on Tombs’ The War Against Paris, 1871, (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1981) which tells the same story from the perspective of the government and army of Versailles. (N.B. Its glossary firmly defines a pétroleuse as a ‘female Communard fire-raiser (imaginary)’ and a fuséen as the male version of the same, also imaginary.)

See also Tombs’ articles, ‘Prudent Rebels: the 2nd Arrondissement during the Paris Commune of 1871′ in French History (1991), 5, (4), pp393-413; ‘The Thiers Government and the Outbreak of Civil War in France, February-April 1871, The Historical Journal, 23, 4, (1980), pp 813-831 and Karine Varley’s interesting commentary on Robert Tombs’s “How Bloody was la Semaine Sanglante? A revision,” H-France Salon, vol. 3 issue 1: 1-13 and Society for French Historical Studies Conference Panel “Communal Myths?”12 February 2011 offering caveats on Tombs’ reduced estimates of total numbers killed during the final week of the Commune. Tombs originally calculated 20,000 rather than 25,000 and then lowered this to between 6,000 and 7,500. Varley also examines recent thinking on the workings of collective memory, and how and why ‘collective amnesia’ may have operated in the aftermath of the Commune.

Alistair Horne offers a squarely conservative take in The Fall of Paris: The Siege and the Commune, 1871, (London: MacMillan, 1965; revised, Penguin Books, 2007 & adapted and jazzed up with excellent but infuriatingly sourceless illustrations for the centenary in 1971 as The Terrible Year: The Paris Commune, 1871) Well-written but often incredibly annoying, particularly when it comes to women. The same applies to…

…Rupert Christiansen, Paris, Babylon: Grandeur, Decadence & Revolution, 1869-1875, (Pimlico, 2003)

Stewart Edwards, The Paris Commune, 1871 (London: Eyre & Spottiswoode, 1971) Out of print but second-hand copies widely available.

Edwards also edited and introduces an illustrated collection of extracts from documents relating to the PC, part of the Documents of Revolution series, The Communards of Paris, 1871 (London: Thames & Hudson, 1973)

[Frank Jellinek, The Paris Commune of 1871 – I know I should have read this but I’m afraid I didn’t.]

Martin Phillip Johnson, The Paradise of Association: Political Culture and Popular Organizations in the Paris Commune of 1871 (Anne Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1996)

Colette E. Wilson, Paris and the Commune, 1871–78: the Politics of Forgetting, (Manchester, Manchester University Press, 2007) A brilliant book on myth-making and memory in the immediate aftermath of the Commune – great on Zola, Le Monde Illustré, and ruin photography.

Kristin Ross, The Emergence of Social Space: Rimbaud and the Paris Commune, 1988, (Verso, 2008), foreword by Terry Eagleton. ‘Bastard thought’, bricolage, the carnivalesque…history/theory/literature…

Andrew Eschelbecher, ‘Environment of Memory: Paris and Post-Commune Angst‘ in Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide, Vol 8, Issue 2, Autumn 2009.

Patrick C. Jamieson, ‘Criticisms of the 1871 Paris Commune: The Role of British and American Newspapers and Periodicals,’ intersections 11, no. 1 (2010): 100-115

Gordon Wright, ‘The Anti-Commune: Paris, 1871’, French Historical Studies, Vol. 10, No. 1 (Spring, 1977), pp. 149-172

Bertrand Taithe, Defeated flesh: Welfare, warfare and the making of modern France, (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1999)

Mark Traugott, The Insurgent Barricade, (University of California Press, 2010)

Jill Harsent, Barricades: The War of the Streets in Revolutionary Paris, (Palgrave Macmillan, 2002)

Gaston Gordillo, Bringing the Paris Commune Back to LIfe (Space and Politics blog, 29 May 2013)

Paul Mason on Why it was Kicking off Then (History Workshop Online)

Alice Bullard, Exile to Paradise: Savagery and Civilization in Paris and the South Pacific (Stanford University Press, 2000)

Alex Butterworth, The World that Never Was: a True Story of Dreamers, Schemers, Anarchists and Secret Agents, (London: Vintage, 2011) – good on Communards in exile.

Jackdaw folders were my first introduction to historical primary sources as a child. I managed to find a second-hand copy of Jonquil Anthony’s The Siege of Paris & The Commune (nd) Jackdaw No.59 which filled me with nostalgia as well as being useful.

Women in the Commune

Pioneering French historian Edith Thomas led the way on women in the Commune, pricked to her task by the misogynistic and reactionary views expressed by Maxime du Camp and many others from both sides of the political fence (including Lissagaray and Marx!).

Pioneering French historian Edith Thomas led the way on women in the Commune, pricked to her task by the misogynistic and reactionary views expressed by Maxime du Camp and many others from both sides of the political fence (including Lissagaray and Marx!).

Here’s an extract from a du Camp’s testimony:

‘The weaker sex behaved scandalously during those deplorable days…The story of their folly ought to titillate the talents of a moralist or alienist [ie psychiatrist]. They tossed much more than their caps over windmills; not stopping at this minor detail, all the rest of their clothing followed. They bared their souls, and the amount of natural perversity revealed there was stupefying. Those who gave themselves to the Commune — and there were many — had but a single ambition: to raise themselves above the level of man by exaggerating his vices. There they found an ideal they could achieve. They were venomous and cowardly. . . They were all there, agitating and squawking. . .What was profoundly comic was that these absconders from the workhouse unfailingly invoked Joan of Arc, and were not above comparing themselves to her. . . During the final days, all of these bellicose viragos held out longer than the men did behind the barricades. . . Many of them were arrested, with powder-blackened hands and shoulders bruised by the recoil of their rifles; they were still palpitating from the overstimulation of battle. . .’ Les Convulsions de Paris, Vol 2, pp 86-90.

So Thomas wrote Les Pétroleuses in 1963, which was translated into English by James and Starr Atkinson and published in the US in 1966 and the UK in 1967 as The Women Incendiaries. Her maternal grandmother had been an artificial flower-maker who supported the Commune, though her paternal grandmother was on the side of Versailles, and Thomas reported from Barcelona and the Pyrenees during the Spanish Civil War, and was active in the Resistance. Towards the end of her life, she wrote a biography of Michel, posthumously-published: this recognises Michel’s tendencies towards fictionalising her own life and is emphatically not a hagiography.

Louise Michel was translated (by ‘P.W.’) and published by Black Rose Books, Montreal in 1980.

The Red Virgin: Memoirs of Louise Michel, ed. and trans. by Bullitt Lowry & Elizabeth Ellington Gunter (University of Alabama Press, 1981)

Gay Gullickson analyses the representation of Communardes – pétroleuses and ministering angels, amazon warriors, scandalous orators and innocent victims – in the very readable Unruly Women of Paris: Images of the Commune (Ithaca & London: Cornell University Press, 1996)

Caroline Eichner uses case studies of three other prominent Communardes – André Leo, Elisabeth Dmitrieff and Paule Mink – to investigate the different forms taken by feminist socialism in the decade before the Commune, and the effect of these varied politics on fin-de-siècle gender and class relations: Surmounting the Barricades: Women in the Paris Commune, (Bloomington & Indianapolis: Indiana University Press, 2004)

Louise Michel: Rebel Lives, series ed. Nic Maclellan, (Melbourne & NY: Ocean Press, 2004) is a mixture of autobiographical extracts and commentary

Other references and articles:

Bertrand Tillier article (in French) on The myth of the pétroleuses

Francine du Gray, Rage & Fire: A Life of Louise Colet, Pioneer Feminist, Literary Star, Flaubert’s Muse, (London: Hamish Hamilton, 1994)

Marie Marmo Mullaney, ‘Sexual Politics in the Career and Legend of Louise Michel,’ Signs 15 (1990): 300-322

Kathleen Hart, Revolution and Women’s Autobiography in Nineteenth-century France, (Editions Rodopi, 2004)

John Simkin’s short biography of Anna Jaclard at the (always useful) Spartacus website

Lynda Nead Gresham Lecture, Fashion and Visual Culture: Women in Red

Much though I hate to lump women with children, for obvious reasons, if I don’t, you might miss this fascinating (open source) article on children in the Commune by André Thomas: ‘The Lost Children of the Commune‘

NEW ADDITION: Mary M Talbot and Bryan Talbot have published a graphic biography of Michel called The Red Virgin and the Vision of Utopia (Jonathan Cape, 2016). I’ve reviewed it here.

Contemporary (eye-witness) accounts

Pro/neutral:

Prosper-Olivier Lissagaray, History of the Commune of 1871, trans. by Eleanor Marx Aveling, revised edition with forward by Eric Hazan. (Verso, 2012) First published in Brussels in 1876, and banned in France, first published in English in 1886. Eleanor Marx’s introduction sums up ‘the true meaning of this Revolution’ in a a few words: ‘It meant the government of the people by the people. It was the first attempt of the proletariat to govern itself.’

Victorine Brocher, Souvenirs d’une morte vivante, (1909)

Maxime Vuillaume, Mes Cahiers Rouges au Temps de la Commune, 1900. (At internet archive.)

Satter-Laumann, Histoire d’un Trente Sous (1870-71), (Paris, 1891)

Louis Barron, Sous le drapeau rouge [and here on The Deportation to New Caledonia.]

Gaston Cerfbeer, Une Nuit de la Semaine Sanglante, Revue Hebdomadaire, (Paris, 1892) – memories of a 12 year old during Bloody Week.

Paul Ginisty, Paris Intime en révolution, 1871, (Paris, 1904)

Edward Bowen was an influential schoolmaster at Harrow School, author of the song ‘Forty Years On’ who was in Paris during the Easter holidays of 1871, and delivered what must have been a rousing lecture on the subject to the Harrow Liberal Club on October 31st, 1887. It’s published in his 1902 A Memoir.

(‘Would you rather have been Delescluze who fell on the barricade in a ruined cause, or the Marquis Galliffet, who shot old men and women as they marched along in the ranks of the prisoners to Versailles, and is now an honoured and decorated general?. . . So ended an experiment in political government which seems to be more dramatic in interest and more fertile in instruction than the history of any similar period that I know. These things happened 16 years ago in the most cultured capital in Europe. As there are no books on the subject which are even approximately truthful, I have thought it worth while to put together an outline of the facts…I am not now going to ask you which party was in the right in a contest where one side wrote on their standard ‘The Unity of France’ and the other ‘The Rights of the People’. There are few struggles and I am not prepared to say that this is one – where virtue, loyalty and wisdom are all combined and banded against their opposites.’

Neutral/anti:

Bertall, The Communists of Paris, 1871, Types, Physiognomies, Characters, With Explanatory Text descriptive of each Design written expressly for this Edition, By an Englishman, Eye-witness of the Scenes and Events of that Year. (Popular English Edition, 1973)

John Furley, Struggles and Experiences of a Neutral Volunteer, (London: Chapman and Hall, 1872) (Good map of Paris and environs)

W. Pembroke Fetridge, The Rise and Fall of the Paris Commune in 1871; with a full account of the bombardment, capture, and burning of the city, illustrated with a wonderful map of Paris and portraits from original photographs, (New York: Harper & Bros, 1871)

Rev. W. Gibson, Paris During the Commune, (London, 1895)

Insurrection in Paris, Related by an Englishman (Davy?), (Paris, 1871).

John Leighton, Paris Under the Commune Or, The Seventy-three Days, (1871)

(extract: One Day Under the Commune)

F. Adolphus, Some Memories of Paris, (Edinburgh & London, Blackwood & sons, 1895) – Chapter 7.

MacMillan’s Magazine, 1871, Vol 24, ‘A Victim of Paris and Versailles’

Léonce Patry, The Reality of War: A Memoir of the Franco-Prussian War and the Paris Commune (1870-1) by a French officer, translated with a foreword and notes by Douglas Fermer

Diary (and papers) of Edwin Child at King’s College, London: MS.26/A2 DIARY 1871

(‘What a disgrace for poor France, almost ruined by an implacable enemy, and then brought to the verge of destruction by its own children, somebody is to blame but who?…I am getting heartily sick of this country and its inhabitants. “a house divided against itself must fall” and such seems the state of this country, after 20 years of flattery and corruption unequalled in history and to think that people are still to be found who pity Napoleon, a man or scoundrel worthy of the contempt of every right thinking individual’ From Child to his father, 11th April 1971)

Augustine Blanchecotte, Tablettes d’une femme pendant la Commune,1872. [‘Mes Tablettes n’ont aucune prétension d’aucun genre; elles représent l’aspect d’une ville, comme la photographie reproduit les ruines.’]

Louis Énault, Paris Brulé par la Commune, (Paris, 1871) – illustrated with 12 engravings from photographs

Ernest Alfred Vizetelly, My Adventures in the Commune (London: Chatto & Windus, 1914)

***

Anthology in French: 1871: La Commune de Paris, ed. Nicole Priollaud, (Paris, Liana Levi, 1983) – includes Duman, Hugo, Ibsen, George Sand, Verlaine.

Anthology in English: Communards: The Story of the Paris Commune of 1871, As Told by those Who Fought for It. Texts selected, edited and translated by Mitchell Abidor. Pub by Marxists Internet Archive Publications/Erythrós Press, 2010. (See below.)

Photography & other visual sources

The Siege and Commune of Paris, 1870-1871, Charles Deering McCormick of Special Collections, Deering Library, Northwestern University: links to over 1200 digitised photographs and images recorded during the Siege and Commune.

Quentin Bajac, ed. La Commune photographiée. With essays by Alisa Luxenberg, Stéphanie Soutteau, and Denis Pellerin (Paris: Éditions de la Réunion des musées nationaux, 2000)

Nancy Brokaw, “Aux Morts de la Commune: Photographs from the Paris Commune of 1871” (2001) This essay first appeared in The Photo Review, 24:4 (Fall 2001), pp. 6-10, 22.

Przyblyski, Jeannene M. Revolution at a Standstill: Photography and the Paris Commune of 1871.New Haven: Yale University Press, 2001

Donald English ‘Political Photography and the Paris Commune of 1871: the photographs of Eugene Appert,’ History of Photography, vol 7 no. 1, janvier 1983

Eric Fournier, ‘Photographs of the ruins of Paris in 1871, or the pretences of pictures’, Revue d’Histoire du XIXe Siècle, 32, 2006, pp137-151 – online.

Hollis Clayson, Paris in Despair: Art and Everyday LIfe under Siege (1870-71) (London & Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2002) [NB Clayson is avowedly apolitical in approach, careful to avoid polemic]

Morna Daniels ‘Caricatures from the Franco-Prussian War of 1870 and the Paris Commune’ – on British Library website.

American photographers Scully & Osterman offer a comprehensive Q & A on collodion and other early photography techniques.

The era’s obsession with physiognomy came up in so many different texts and images – I found this Getty blog a useful introduction to the subject.

Here’s a good selection of photographs by Bruno Braquehais.

Two stunning illustrated exhibition catalogues:

Charles Marville, Photographer of Paris, by Sarah Kennel, with Anne de Mondenard, Peter Barberie, Françoise Reynaud, Joke de Wolf (National Gallery of Art, Washington; Chicago & London: University of Chicago Press, 2014)

Impressionism, Fashion & Modernity, ed. Gloria Groom (New Haven & London: Yale University Press, 2012) (Very useful for finding out about elastic-sided boots, Worth, and where the best cut shirts could be bought.)

And Henry Sara’s Lantern Lectures

Music

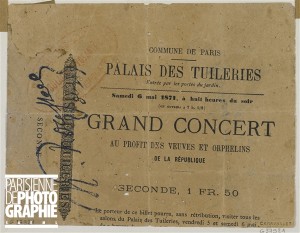

Delphine Mordey’s Moments musicaux: high culture in the Paris Commune, (Cambridge Opera Journal, 22, 1, 1-31) started me thinking about music in Liberty’s Fire, introduced me to the Commune’s spectacular fund-raising concerts, and led me to most of the other material listed here, most importantly her PhD, ‘Music in Paris, 1870-71′, Cambridge University, 2006.

In summary, in staging (or attempting to stage) musical events at the Tuileries and the Opéra, the workers’ government ‘frequently described. . .as barbaric and primitive, sought legitimation through the appropriation of the space and culture of the ousted ruling classes. Ultimately this plan would backfire: far from being taken seriously, the Communards would be described by their critics as little more than characters in their own operatic drama.’

Mordey, D,'”Dans le palais du son, on fait de la farina”: Performing at the Opera during the 1870 Siege of Paris’, Music & letters, 93, No 1, 2012, 1-28 — Oxford University Press

Music in Paris during the Franco-Prussian War and the Commune

Jess Tyre, ‘Music in Paris during the Franco-Prussian War and the Commune, The Journal of Musicology, Vol. 22, No. 2 (Spring 2005), pp. 173-202 (but note Mordey’s caveats re Tyre’s confusion between the Fédération Artistique and the Fédération des Artistes)

Gonzalo J Sánchez, Organizing Independence: The Artists Federation of the Paris Commune and Its Legacy, 1871-1889 (University of Nebraska Press, 1997)

T J Walsh, Second Empire Opera: The Théâtre Lyrique, Paris 1851-1870, (London: John Calder, 1981)

Albert de Lasalle, Mémorial du Théâtre Lyrique, (Paris, 1877)

You’ll find all the most popular songs connected with the Commune, including Le Temps des Cerises, La Canaille, and the Internationale here, in a collection of ‘chansons historiques de la France’ which helpfully includes history and lyrics as well as good slideshows.

Nineteenth-century Paris

Stephane Kirkland, Paris Reborn: Napoléon, Baron Haussmann and the Quest to Build a Modern City, (St Martin’s Press, New York: 2013

Stephane Kirkland, Paris Reborn: Napoléon, Baron Haussmann and the Quest to Build a Modern City, (St Martin’s Press, New York: 2013

Eric Hazan, The Invention of Paris: A History in Footsteps, (Verso, 2011) – and a good review by Adam Thorpe.

Henri D’Almeras, La Vie Parisienne pendant le Siège et sous la Commune, (Paris: Albin Michel, 1927)

Sharon Marcus, Apartment Stories: city and home in 19th-century Paris and London, (University of California Press, 1999)

Ann-Louise Shapiro, Housing the Poor of Paris, 1850-1902, (University of Wisconsin Press, 1985)

W. Scott Haine, Sociability among the French Working Class, 1784-1914 (Baltimore & London: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 1996) (very good on the world of the Paris café)

Walter Benjamin, The Arcades Project, trans. by Howard Eiland and Kevin McLaughlin, prepared on the basis of he German volume ed. by Rolf Tiedemann, (Cambridge, Mass. & London: Harvard University Press, 1999)

(This article will give you some idea why Benjamin was important for Liberty’s Fire.)

Miranda Gill, Eccentricity and the Cultural Imagination in Nineteenth-Century Paris, (OUP, 2990)

Jill Harsin, Policing Prostitution in Nineteenth-Century Paris, (Princeton, New Jersey, 1985)

Christopher Prendergast, Paris and the Nineteenth Century, (Blackwell, 1992)

Maxime du Camp, Paris – Ses Organes, ses fonctions et sa Vie, dans la seconde motié du XIXe siècle, (Paris: 1874)

I can’t pretend to have read every word, but Vol 5 was very useful on the subject of the Mont de Piété, Vol 2 on Les Halles, and Vol 3 on prostitution.

The University of Chicago offers an impressive selection of digitised 19th-century maps of Paris. I used this one: Scale 1:10,000. Paris : E. Andriveau-Goujon, 1869. 1 map : hand col. ; 92 x 142 cm., on sheet 102 x 150 cm.

Homosexuality in nineteenth-century Paris

Michael D. Sibalis, ‘Paris’ in Queer Sites: Gay Urban Histories since 1600, ed. David Higgs, (London & NY: Routledge, 1999)

Graham Robb, Strangers: Homosexual Love in the Nineteenth Century, (London: Picador, 2003)

Alke van den Berg, What is to be found in the eyes of a stranger? Comparing the Cruiser and the Flâneur (online essay)

Judy Greenaway, Enemies of the State? Homosexuality in the Nineteenth Century (pub. in Anarchist Studies, 13:1, 2005, pp90-95 analyses Graham Robb’s Strangers and Matt Cook’s London and the Culture of Homosexuality, 1885-1914, (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2003) in relation to late nineteenth-century anarchism.

Fiction

Jules Vallès, Jacques Vingtras: L’Insurgé – the last of an autobiographical trilogy written in exile in London by the Communard journalist who edited one of the most successful newspapers of the Commune, Le Cri du Peuple. Read it online in French or English.

Emile Zola, The Belly of Paris (trans. Mark Kurlansky), Nana, L’Assommoir, The Debacle.

Flaubert, A Sentimental Education (NB set during the 1848 revolution)

Maupassant short stories, especially Boule de Suif, a fantastically sharp portrayal of class loyalties and sexual politics set during the Franco-Prussian war.

Jean Vautrin, translated by John Howe, The Voice of the People (London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson, 2002) This was first published in France in 1999 as Le cri du people, and adapted by Tardi into a beautiful graphic novel – though I’ve only seen the first part, Les canons du 18 Mars.)

Jean-Baptiste Clément & Philippe Dumas, Le Temps des Cerises, (Paris: l’école des loisirs, 1990) An exquisite picture book in which Dumas tells the story of the Commune in pictures to the text of Clément’s famous song, and includes a portrait of the worker-songwriter and this short biography: ‘Jean-Baptiste Clément (1838-1903) fought on the barricades during ‘Bloody Week’, the title of one of his poems. He had already written Le Temps des Cerises in 1866, set to music by Renard. Escaping from the Versaillais, he took refuge in London after the defeat of the Commune. He returned to France after the 1880 Amnesty Law and worked in Jules Guesde’s Parti-ouvrier socialist francais – the French Workers’ Party.

Guy Endore,The Werewolf in Paris (1933) is a compelling read on multiple counts, a horror classic which is historically accurate and based on sources I used myself (such as Mes Cahiers Rouge – see above). It concludes that the horrors of Bloody Week demonstrate that we are all monsters under the skin, implicitly looking forward from 1871 to the devastation and madness of World War One. You’ll find an interesting review by Michael Dirda of the Washington Post here of a new edition, and an excellent analysis of the politics of the novel and the author here by Carl Grey Martin. Endore was a Hollywood screenwriter and it might not surprise you to learn that he was blacklisted in the 50s.

Guy Endore,The Werewolf in Paris (1933) is a compelling read on multiple counts, a horror classic which is historically accurate and based on sources I used myself (such as Mes Cahiers Rouge – see above). It concludes that the horrors of Bloody Week demonstrate that we are all monsters under the skin, implicitly looking forward from 1871 to the devastation and madness of World War One. You’ll find an interesting review by Michael Dirda of the Washington Post here of a new edition, and an excellent analysis of the politics of the novel and the author here by Carl Grey Martin. Endore was a Hollywood screenwriter and it might not surprise you to learn that he was blacklisted in the 50s.

(‘..now is the time of monsters’…other connections between the Commune and the horror genre are convincingly made in Eric D Smith’s ‘”A Presage of Horror“: Cacotopia, the Paris Commune and Bram Stoker’s Dracula’, Criticism, Vol 52, no. 1, Winter 2010. Interestingly, the literal translation of Communarde Victorine B’s memoir, Souvenir d’une morte vivante – see above – could be ‘Momento of a female zombie’ or ‘Recollections of the living dead’, which also conveys the sense of a transforming tide or infection that turns human beings into destructive monsters.)

Isak Dinesen (Karen Blixen), Babette’s Feast, 1953.

Chapter IV: ‘The bearer of this letter, Madame Babette Hersant, like my beautiful Empress herself, has had to flee from Paris. Civil war has raged in our streets. French hands have shed French blood. The noble Communards, standing up for the Rights of Man, have been crushed and annihilated. Madame Hersant’s husband and son, both eminent ladies’ hairdressers, have been shot. She herself was arrested as a Pétroleuse–(which word is used here for women who set fire to houses with petroleum)–and has narrowly escaped the blood-stained hands of General Gallifet. She has lost all she possessed and dares not remain in France.’

[Dinesen’s father Wilhelm, a French army officer at the time, was a sympathetic eye-witness to the Commune; his account of events was translated into French from Dutch in 2004.]

Edward Bulwer-Lytton, The Parisians, 2 vols, 1873. Frustratingly unfinished and doesn’t quite make it to the Commune, but an interesting picture of Paris in the build-up to the Franco-Prussian war. Predictable politics from the aristocrat who coined the phrase ‘the Great Unwashed’ in another novel, Paul Clifford, which spawned the ‘dark-and-stormy-night’ annual fiction contest.

G.A.Henty, A Girl of the Commune, 1895

Fanny Surtees (Cherith), ‘Rachel, the Pétroleuse’, (London, 1878) A deeply anti-socialist and anti-Republican evangelical story in which the rebellious and consequently ruined maid is taught by a good Englishwoman and a passing priest to fear God and honour the King.

James Cobb, In Time of War: a tale of Paris life during the siege and the rule of the Commune, (London, 1883) [Sample: ‘”I wish men would attend to their work and not so much to politics.” “Yes, Marie, you are right,” said the old woman, with a sigh, “that has been the cause of all our troubles, our men being never satisfied, and always wanting change; their minds being filled with evil notions and revolutionary ideas. Alas! Alas!” and the old woman load down her knitting and a very sorrowful expression came over her face.’]

Mrs John Waters, A young girl’s adventures in Paris during Commune, (London, 1881)

[Utterly preposterous, hideously inaccurate, extremely anti-Commune.]

Jules Claretie, Agnès – A Romance of the Siege of Paris, trans. Ada Solly-Flood, 1909.

I wish I’d come across Eustace Clare Grenville Murray‘s French Pictures in English Chalk, Vol 1 and Vol 2, (1876) while I was writing Liberty’s Fire. Vol 2 even has a story about a pétroleuse on trial and a character called Zephirine who sings at the Théâtre des Fantaisies Comiques! (p. 126 At the theatre Monsieur Javelin introduces her to Monsieur Semolina with these words: ‘”I advise you to beware of Mdlle. Zephirine. She has broken the hearts of two stage managers, and hurried fifteen fiddlers out of the orchestra to an early grave. Her policy in life is never to learn her parts, and to sing the music as she fancies. There is a particular flute-player who has grown asthmatic from trying to keep pace with her.”‘)

SEE ALSO ‘New Material’, below, for other suggestions.

Museums and places in Paris

Musée de l’histoire vivante, Montreuil (You’ll need to make an appointment to see the magnificent Commune collection.)

Musée d’art et histoire de Saint-Denis

Musée Francais de la Photographie (PLEASE phone to check this is open. I didn’t, as you will know if you read this History Girls post on the subject. Still hoping to get there…)

Hôtel de Ville, Paris

Père Lachaise cemetery and the Mur des Fédérés

Some melted bits of the Tuileries Palace can be see at the Musée des Arts Décoratifs

You can find out more about the Franco-Prussian war at the Musée de l’Armée at the Invalides, but don’t expect any mention of the Semaine Sanglante, or the army’s role in crushing the Commune!

Some extremely useful online archives & bibliographies

Paris Commune Collection at University of Sussex Special Collections – although this catalogue page is no longer updated and subject to change, it’s still the easiest way to get a sense of the scope of the collection, so I’m including it here although visitors are referred to the new pages at the Keep in the hope that the link doesn’t disappear too soon as threatened! Ditto this summary.

Introduction to British Library collection on Franco-Prussian War and Commune

Annotated bibliography by Sharif Gemie

Left on the Shelf – An excellent but not quite up-to-date bibliography of works in English on the Commune by David Cope, an extremely experienced radical bookseller.

Marxist Internet Archive including a very useful TIMELINE.

https://libcom.org/library – alongside contemporary politics, this site offers an excellent, easily searchable resource for the history of anarchism including this biography of N.F.Dryhurst

Association des Amies et Amis de la Commune de Paris, 1871 – news, events and history.

Raspouteam’s 2011 project for the 140th anniversary of the Commune is packed with day to day detail, archive material and images of important Commune sites today.

Paris en Images – access to over 80,000 images from the Roger-Viollet archive as well as the collections of the Paris Historical Library, the City Hall Library, Forney graphic arts Library, Musee Carnavalet or the collection of photographer Pierre Jahan, among others.

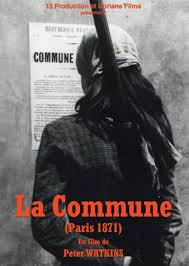

Peter Watkins’ film La Commune (Paris 1871)

New material

‘Afterlives of the Commune’ by Francis Mulhern – review of Kristin Ross’ Communal Luxury in New Left Review.

Listen to a potted history of the Commune as told by spoken word artist Paul Case a.k.a Captain of the Rant at The Rebel Chronicles

Luc Sante, The Other Paris: an illustrated journey through a city’s poor and bohemian past, (Faber, 2015)

A new book by Elisabeth Jay, British Writers and Paris, 1830-1875 (OUP, Jan 2016) has an interesting section on responses to the Commune (pp43-50), including analysis of Eliza Lynn Linton’s moral fable, The True History of Joshua Davison, Christian and Communist (1872), whose narrator claims that ‘the Commune’s selfless cooperation and self-government wrote “one of the brightest pages of modern history”‘. This novel features an English prostitute shot on the barricades as a pétroleuse. Matilda Betham-Edwards‘s anti-Jesuit novel Brother Gabriel (1878) nods to the glory of France’s aspirations but still dismisses a working-class election-day rabble as ‘a veritable human scum’. Mary Elizabeth Braddon‘s Under the Red Flag (1883) addresses ‘a similarly paternalist agenda’ to that of Bulwer Lytton’s The Parisians (see above), condemning misguided aristocratic radicals and journalists and casting a ‘unsexed’ she-devil called Suzon Michel(!) as ‘the villain of the piece’. Two years later Anne Thackeray Ritchie’s young socialist hero is repulsed by the ‘”wild saturnalia of the streets, where dishevelled women were dancing round the flames”‘ in Mrs Dymond (1885). She points out that Arnold Bennett’s account of the Siege and Commune in The Old Wives’ Tale owes more to Flaubert’s L’Education Sentimental (see above – about the 1848 revolution) than historical sources or the account given to him by an elderly, working-class French couple. British poetry about the Commune is scanty: for Jay, the personal overwhelms the political in William Morris’s ‘The Pilgrims of Hope‘, while in The Red Flag and Other Poems, Roden Noel denounces the extermination of the Communards but is mostly concerned with social divisions in London.

Gavin Bowd, The Last Communard: Adrien Lejeune, the unexpected life of a revolutionary (Verso, 2016), looks not just at the life of a rather reluctant Communard, but the construction of the legend that grew around it, and Lejeune’s role as ‘the last tangible link between the nineteenth-century French revolutionary tradition and the Soviet Union’ (according to Robert Tombs). A Lissagary quotation serves as a admonitory epigraph: ‘Whoever creates for the people false revolutionary legends, who amuses them with enchanting stories, is as criminal as the geographer who makes untruthful maps for navigators.’

Mary M Talbot and Bryan Talbot, The Red Virgin and the Vision of Utopia, (Jonathan Cape, 2016) is an excellent ‘graphic biography’ of Louise Michel, reviewed by me here.

Paul Mason’s play about Louise Michel and her life in exile in New Caledonia, The Divine Chaos of Starry Things, produced in May 2017 at the White Bear, Kennington, sadly fails dismally as theatre despite the best efforts of its cast, but his research on the ground and in the Pacific archives sheds interesting new light on this period and is well worth reading. (See also Alice Bullard, above.)

Category Reviews & more | Tags: 1871, Books about Paris Commune, Citoyennes, Communardes, Communards, Franco-Prussian War, further reading, Liberty's Fire, Lissagaray, Louise Michel, Paris Commune, Paris Commune bibliography, photography, reading list, Revolution, Siege of Paris, Vallès, Women

ck5cceu