The cave hospital, at last.

0September 27, 2013 by Lydia Syson

‘This hospital is in a cave. When Felix heard, she imagined a storybook kind of cave, where dragons lurk on piles of gold at the end of winding tunnels. Theirs is a great horizontal gash in the rock face of a hillside, an unhappy open mouth. But its roof is solid stone. And it won’t be far from the fighting.

‘On uneven rocky floors the orderlies have done their best to recreate a ward, with staggered lines of camp beds on several levels. At one end is the food store, and the kitchen – a scrubbed wooden table and a vast cauldron bubbling on a fire, big enough to feed a coven of witches. A few stone walls, built like the terraces that step down to the valley below, offer more protection.

‘On uneven rocky floors the orderlies have done their best to recreate a ward, with staggered lines of camp beds on several levels. At one end is the food store, and the kitchen – a scrubbed wooden table and a vast cauldron bubbling on a fire, big enough to feed a coven of witches. A few stone walls, built like the terraces that step down to the valley below, offer more protection.

‘Kitty and Felix climb back up the stoney path to the cave.  In the olive grove, they pass the triage tent – the equip – and the transfusion lorry. A group of men in vests and dungarees are busy getting stretchers ready. Piles of wooden poles lie waiting to be fed through canvas. Trucks and ambulances nearby have bonnets up, and legs stick out from under chassis, as drivers carry out last-minute checks and repairs. The vehicles have a dead, hollow feel to them without their windscreens. Some have been smashed out by bombs, the others removed on purpose. The flash of sun on glass is an instant giveway to the enemy air force. Even moonlight shows up a windscreen.’

In the olive grove, they pass the triage tent – the equip – and the transfusion lorry. A group of men in vests and dungarees are busy getting stretchers ready. Piles of wooden poles lie waiting to be fed through canvas. Trucks and ambulances nearby have bonnets up, and legs stick out from under chassis, as drivers carry out last-minute checks and repairs. The vehicles have a dead, hollow feel to them without their windscreens. Some have been smashed out by bombs, the others removed on purpose. The flash of sun on glass is an instant giveway to the enemy air force. Even moonlight shows up a windscreen.’

A World Between Us, pp. 229-230

I’m always envious of writers who have the luxury of travelling to all the settings of their fiction, breathing in the smells, feeling the textures of actual places and the quality of the air. Tramping round Romney Marsh and absorbing its peculiar atmosphere was an important part of writing That Burning Summer which is coming out this Thursday. But when I was working on A World Between Us, I had neither the time, money nor confidence of certain publication to travel to all the different places Felix, Nat and George find themselves in the course of the book. My biggest regret was not being able to get to the cave hospital near the village of La Bisbal de Falset in Catalonia, where Felix is stationed in early summer, 1938, during the preparations for the planned Ebro offensive.

Last Saturday, thanks to the tour of the region organised by the International Brigade Memorial Trust to commemorate the British Battalion’s involvement in this battle, my ambition was finally realised. I was both nervous and excited as the coach wound its way up from the river Ebro – a far longer journey than I’d imagined. Of course seventy-five years ago it would have felt longer and bumpier still for the wounded soldiers who travelled in battered ambulances or on the backs of mules, on bomb-cratered roads, enemy aircraft always overhead. They would have already endured an arduous and terrifying river crossing, rowed across at night in local boats, or brought across the few pontoons which hadn’t been swept away when Franco’s forces opened the floodgates just a few days into the attack.

Last Saturday, thanks to the tour of the region organised by the International Brigade Memorial Trust to commemorate the British Battalion’s involvement in this battle, my ambition was finally realised. I was both nervous and excited as the coach wound its way up from the river Ebro – a far longer journey than I’d imagined. Of course seventy-five years ago it would have felt longer and bumpier still for the wounded soldiers who travelled in battered ambulances or on the backs of mules, on bomb-cratered roads, enemy aircraft always overhead. They would have already endured an arduous and terrifying river crossing, rowed across at night in local boats, or brought across the few pontoons which hadn’t been swept away when Franco’s forces opened the floodgates just a few days into the attack.

The Battle of the Ebro was the Spanish government’s l ast great effort to win back the territory lost in the retreats of spring 1938 (see AWBU, pp 211-218), when the Nationalist rebels had broken through to the Mediterranean, dividing Republican territory in two, and establishing the river as a frontline. Alun Menai Williams, a sanitario (medic) with the British Battalion described it as ‘Twelve weeks of organized, unyielding, mass slaughter.’

ast great effort to win back the territory lost in the retreats of spring 1938 (see AWBU, pp 211-218), when the Nationalist rebels had broken through to the Mediterranean, dividing Republican territory in two, and establishing the river as a frontline. Alun Menai Williams, a sanitario (medic) with the British Battalion described it as ‘Twelve weeks of organized, unyielding, mass slaughter.’

I felt extremely privileged to be able

I felt extremely privileged to be able  to participate in a ceremony organised by No Jubilem La Memòria celebrating the restoration of a (sadly vandalised) plaque commemorating all the British medical personnel who worked in the cave in 1938. Villagers and visitors from Britain, Ireland, America, Portugal and Puerto Rico were welcomed by the mayor of La Bisbal de Falset, Sergi Masip, who introduced his predecessor, Enric Masip. He remembered being taken to the hospital at the age of 5 by his uncle, about ten years after the war had ended. It was all overgrown and forgotten, but the spring which had provided the hospital’s water supply still flowed, and maintained its healing reputation. (It is dedicated to St Lucia, patron saint of sight.) We learned of the struggle to reclaim the cave for the village, so that it could become a site of remembrance for local people and the wider world.

to participate in a ceremony organised by No Jubilem La Memòria celebrating the restoration of a (sadly vandalised) plaque commemorating all the British medical personnel who worked in the cave in 1938. Villagers and visitors from Britain, Ireland, America, Portugal and Puerto Rico were welcomed by the mayor of La Bisbal de Falset, Sergi Masip, who introduced his predecessor, Enric Masip. He remembered being taken to the hospital at the age of 5 by his uncle, about ten years after the war had ended. It was all overgrown and forgotten, but the spring which had provided the hospital’s water supply still flowed, and maintained its healing reputation. (It is dedicated to St Lucia, patron saint of sight.) We learned of the struggle to reclaim the cave for the village, so that it could become a site of remembrance for local people and the wider world.

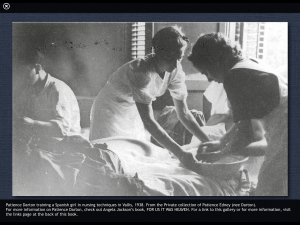

Sadly, Angela Jackson, one of the founders of NJLM, could not be there. Her work on the subject of women in the Spanish Civil War, the cave hospital and nurse Patience Darton who worked here (pictured on the plaque with Spanish nurse, Aurora Fernandez – see also image below) is superb. I felt a poor substitute, but was honoured to give a talk after the ceremony about what it was like to work as a nurse in the cave during the war – valiantly translated by Almudena Cros of the AABI – alongside Peter Crome, son of Len Crome, the chief medical officer of the Republican Army’s 15th Corps, and also Enric Masip,  who explained the rich symbolism of hall in which we spoke. During the repressive Franco era, organising its construction and maintaining it as a communal cultural centre with elected officials was an act of defiance in itself, a way of keeping democracy alive in this small part of Spain at least.

who explained the rich symbolism of hall in which we spoke. During the repressive Franco era, organising its construction and maintaining it as a communal cultural centre with elected officials was an act of defiance in itself, a way of keeping democracy alive in this small part of Spain at least.

My talk went something like this:

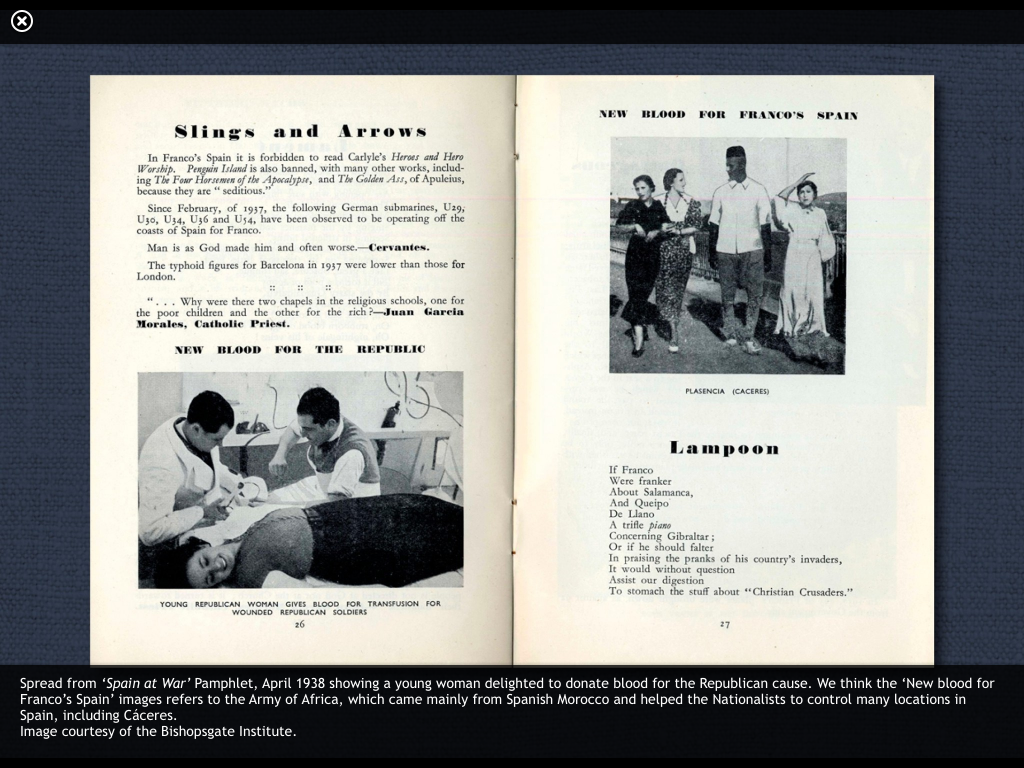

When I began thinking about A World Between Us, all I knew for certain was that my opening had to be at Cable Street – which I knew about from the stories of my grandfather, Jack Gaster. One of the most important advances in medical terms made by the Republican army during the war was in blood collection and transfusion techniques – and this too was something that quickly suggested a powerful narrative thread to me. But as soon as I had listened to the interviews in the Imperial War Musem sound archive with Patience Darton (Edney) and Reggie Saxton (sadly very poor quality sound – but there’s a transcript) – and learned, among other things, of the direct arm-to-arm transfusions that took place right here – this cave hospital fixed itself in my head as the place where I wanted the story to finish. Of course the idea or slogan ‘they gave their blood’ was a vital message in the propaganda efforts of Republican supporters outside Spain. At the time I started writing, teenage fiction was dominated by vampire stories – Twilight etc. Writing about real blood, real sacrifice, in a story rooted in the experiences of real people felt singularly appropriate.

The image of this gash of a cave in the hillside, which sheltered not just Spanish Republican soldiers, Brigaders and local villagers but Nationalist soldiers too – there were a lot of Italian prisoners of war treated here – was particularly rich in symbolism. The experience of working here, at this critical point of the war, seemed to have provoked some of the most intense and vivid descriptions – from nurses, doctors, administrators and visitors.

Last week I went through the notes I’d made three and a half years ago, and re-read Angela Jackson’s book Beyond the Battlefield, and I was struck afresh by the strength of emotion – in accounts of Patience Darton, Leah Manning, Nan Green, Winnifred Bates in particular. The hospital was set up here at a point at which there was much renewed optimism – the Republican army had regrouped for a huge offensive, attempting to retake the ground lost in the retreats. The Ebro offensive was an open secret, and Nan Green, Patience and others all refer to the thrilling sense of growing anticipation, excitement building as roads were widened in the dead of night, local people filled in potholes with branches, and more troops arrived – Nan Green refers to an eerie silence, broken only by the swish of lorries and the chink of metal on rock. The sound which clearly stayed with Patience Darton all her life was that of the soldiers singing – but she talks of them as kids, children – the last call-up, known as the babybottle brigade, were fifteen and sixteen. ‘Can you hear the children singing?’ And she speaks movingly of the contrast between their optimistic voices as they went down to cross the river to the battlefields, and the smashed-up bodies that returned.

She descibes a typical day – actually a typical night, because that was when the injured and dead could most safely be collected, and even with the hospital so close to the fontline, it was still often too late, too long after battle. – so she would try to sleep in the day. She’d get up around 4 in the afternoon, and ‘traipse along’ to her mates, the British drivers, who couldn’t move during the day either. They were a particular support – they’d brew up, and they were good at getting hold of – or ‘organising’ things for the nurses – food, and blood, and medical supplies, and they kept all the machinery going. They were absolutely brilliant improvisers. And when she started work in the evening – there was no dusk, she says, nightfall was sudden and it was pitch dark very early – the first question was always which patients had survived from the night before. Nurses going off would say ‘oh so and so’s alive, or gone’. Joan Purser was another nurse whose interview is in the IWM sound archive: she mentions the cave quite fleetingly, along with the railway tunnel hospitals at Flix, but Patience makes it clear how incredibly valuable she was – ‘one nurse was marvellous – if Joan was on you knew they’d be better when you next saw them.’

Although they had a generator – also kept going by the drivers – and the operating theatre section of the cave could be lit (but I could see no evidence today of where the single lightbulb had once hung) in the ward area the only light came from oil lamps, and it was very hard to see.

As you saw, the ground was very uneven so the metal beds were all higgledy-pickledy – some account say there were 50, some 100, some 150 – and in the dark, the nurses were always banging their shins on them, and tripping over ‘these damn beds’ – they couldn’t get them into straight lines. One of the other advances of this war that’s become standard procedure was a sophisticated system of triage…so patients were ‘sorted’ in tents down below, and the cave received only the very worst cases, that couldn’t be moved any further or needed immediate operations – fractures were plastered up with the new ‘open’ technique and send to rear hospitals.

It was hard to get the patients up the steep path. 50% were without a pulse when they arrived, their veins flat, and the nurses had nothing with which to measure blood pressure. They became very expert at getting needles into collapsed veins – lots of patients needed saline drips or transfusions – and equipment was gradually getting more sophisticated. Most of the injured were mostly headcases, chestcases (not much could be done for them) and abdominals. Unfortunately the abdominals weren’t allowed even water – this was a misunderstanding – torment to arrive thirsty from the battlefield.

Patience describes 4 operating tables with 2 or 3 surgeons working at once through the night – new surgeons were sent from Barcelona to this hospital, because the Brigades’ ‘own’ doctors were up at the front organising evacuation (under Len Crome). There was definitely an issue of trust – I realise looking back at my notes, this must have been what sparked my sabotage plot – as nurses weren’t sure if these new doctors were really on side. ‘We didn’t know what their politics or their quality was’. She says:

‘There were enough of us to make sure subsequent treatment cd be done properly. they did a lot of sabotage on purpose. Like what? Not proper sterility on purpose in the rearguard hospitals because nearly all the doctors were pro-Franco. They got caught on wrong side, and couldn’t resist marvellous surgery. Surgeons can’t resist marvellous surgery’

She then goes on to describe their brilliance at abdominal cases in particular:

‘Spanish surgeons might go through the curls of intestine 20 times – they’d pull them all out and have a look… sometimes they’d cut out a whole lot and join them up. They were very good at that.. sometimes they’d sew them all up. They were marvellous at abdominals.. they’d take out miles and miles of intestine looking for holes from bullets or bits of shrapnel.’

The noises from the patients were clearly incredibly distressing – there was never enough morphia so they weren’t doped enough. The headcases were the worst for noise (‘there was not much you could do except try to keep them still’) and often used to pull their bandaging off – in fact the getting slightly better patients were the hardest to manage – ‘you didn’t want to tie them down, but ended up using up stretcher bearers staying with them.’

Patience remembered one Spanish headcase raving all night, making marvellous political speeches…(here again she referred to the ‘children singing’ in the background). Patience is interesting on the importance of everyone’s different roles. I’ve already mentioned the support nurses had from the drivers. The stretcher bearers were clearly invaluable for reassuring patients – particularly those soldiers who weren’t used to being bossed around by a woman. Many weren’t had never seen an actual doctor before, so they called out for a ‘healer’ – curandera, as Spanish nurse Aurora Fernandez remembered – a wise woman with herbs. Patience describes her team of stretcher bearers as her ‘own trained pets’. But there were internal battles, for example over blankets – because when patients died, the people responsible didn’t want to put them in the earth with nothing round them. It was also easy to lose blankets to patients being evacuated to rearguard hospitals, and then there was also no hope of getting them back.

A lot of the work, other than replacing drips and dressings, was about simple comfort. Just letting patients know you were there. Made so much harder by language barriers. Yiddish was often a useful lingua franca, but a particularly poignant and heartbreaking moment was the death of three Finnish volunteers. As they died, nobody could speak to them in a language they could understand. All three died strapped up, hardly able to breathe, with very deep chest wounds. Patience said: ‘Oh I’ll never forget them. They were such beautiful creatures. Great blonde things.’

Winnifred Bates had a similar reaction as she travelled round the medical units on behalf of the Spanish Medical Aid Committee, checking on the welfare of the nursing staff. She visited the cave hospital in the course of this duty, later using her photographs and descriptions of it very effectively in fund-raising pamphlets:

‘Men died as I stood beside them. It was summer time and they had been in long training before they crossed the Ebro. Their bodies were brown and beautiful. We would bend over to take their last whispers and the message was always the same. ‘Tell them to fight on till the final victory. ‘ It is so hard to make a man and so easy to blast him to death. I shall never forget the Ebro. If one went for a walk away from the cave there was the smell of death.’

Ending on a more positive note, I’ll give the last word to Aurora Ferndandez – who learned her skills from the British nurses – nursing was traditionally done by nuns in Spain before the war, and of course they were rarely on the Republican side. This was the spirit I wanted to convey in my book, that I found so endlessly inspiring:

‘The wonderful team of British doctors and nurses together with the Spanish and other nationalities…never worked in better harmony…The bombing was terrible…We had so many casualties we had to evacuate even the most serious cases. And here again I admired the efficiency of the British team, their spirit of sacrifice. They knew no tiredness, they went on and on, and all of us, as if commanded by the same goal to do our utmost, knew no rest day and night.’

(Download the ‘A World Between Us’ enhanced multi-touch iBook for iPad for more background material about the history behind the novel.)

The communal grave in the village cemetery where many of the dead were buried could not be marked until long after Franco’s dictatorship had ended. We went to lay flowers there, but unfortunately found the gates locked. Richard Baxell, historian of the British Battalion, who gave talks and lectures throughout the tour, as well as answering question after question, is also an expert climber.

Category News | Tags: 35th Division, AABI, Almudena Cross, Angela Jackson, Battle of Ebro, Bisbal de Falset, Cave Hospital, Enric Masip, IBMT, Len Crome, Medicine and war, Nan Green, No Jubilem La Memoria, Patience Darton, Peter Crome, Winnifred Bates

Leave a Reply