Book Genes

0August 5, 2013 by Lydia Syson

Every book has its own peculiar literary heritage, a kind of textual DNA that can be as hard to map as the Genome Project. I’m in danger of muddling my metaphors here, but I thought I’d write today about some of the book genes that have fed into That Burning Summer, books I first read or had read to me so long ago they were half-forgotten when I started writing this new novel. I was vaguely conscious of a few of these influences from the outset; others gradually dawned on me as I wrote, or have even been revealed since.

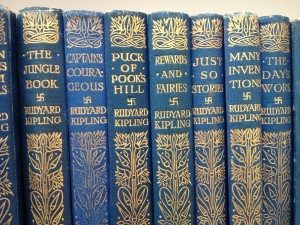

Romney Marsh was a place I knew very well through books long before I ever actually set eyes on it, in my late twenties. When I was very small, my father read a lot of Kipling to me and my brother and sister. Somehow it never occurred to me then that the poems and stories I loved in Puck of Pook’s Hill and Rewards and Fairies were actually about real places I might one day visit.

I ever actually set eyes on it, in my late twenties. When I was very small, my father read a lot of Kipling to me and my brother and sister. Somehow it never occurred to me then that the poems and stories I loved in Puck of Pook’s Hill and Rewards and Fairies were actually about real places I might one day visit.

If you know the tale ‘Dymchurch Flit’, you might remember Ralph Hobden’s magical description of the Marsh ‘back behind of’ Rye:

‘”…there’s steeples settin’ beside churches’ and an’ wise women settin’ beside their doors, an’ the sea settin’ above the land, an’ ducks herdin’ wild in the diks” (he meant ditches). “The Marsh is justabout riddled with diks an’ sluices, an’ tide-gates an’ water-lets. You can hear ’em bubblin’ an’ grummelin’ when the tide works in ’em, an’ then you hear the sea rangin’ left and right-handed all up along the Wall. You’ve seen how flat she is – the Marsh? You’d think nothin’ easier than to walk eend-on acrost her? Ah, but the diks an’ the water-lets, they twists the roads about as ravelly as witch-yarn on the spindles. So ye get all turned round in broad daylight.”‘

‘”…there’s steeples settin’ beside churches’ and an’ wise women settin’ beside their doors, an’ the sea settin’ above the land, an’ ducks herdin’ wild in the diks” (he meant ditches). “The Marsh is justabout riddled with diks an’ sluices, an’ tide-gates an’ water-lets. You can hear ’em bubblin’ an’ grummelin’ when the tide works in ’em, an’ then you hear the sea rangin’ left and right-handed all up along the Wall. You’ve seen how flat she is – the Marsh? You’d think nothin’ easier than to walk eend-on acrost her? Ah, but the diks an’ the water-lets, they twists the roads about as ravelly as witch-yarn on the spindles. So ye get all turned round in broad daylight.”‘

All true, of course. And now I know all the places in it too, the poem ‘Brookland Road’ makes me tingle all the more:

I was very well pleased with what I knowed,

I reckoned myself no fool –

Till I met with a maid on the Brookland Road,

That turned me back to school.

Low down-low down!

Where the liddle green lanterns shine –

O maids, I’ve done with ‘ee all but one,

And she can never be mine!

‘Twas right in the middest of a hot June night,

With thunder duntin’ round,

And I see her face by the fairy-light

That beats from off the ground.

She only smiled and she never spoke,

She smiled and went away;

But when she’d gone my heart was broke

And my wits was clean astray.

O, stop your ringing and let me be –

Let be, 0 Brookland bells!

You’ll ring Old Goodman out of the sea,

Before I wed one else!

Old Goodman’s Farm is rank sea-sand,

And was this thousand year;

But it shall turn to rich plough-land

Before I change my dear.

O, Fairfield Church is water-bound

From autumn to the spring;

But it shall turn to high hill-ground

Before my bells do ring.

O, leave me walk on Brookland Road,

In the thunder and warm rain –

O, leave me look where my love goed,

And p’raps I’ll see her again!

Low down – low down!

Where the liddle green lanterns shine –

O maids, I’ve done with ‘ee all but one,

And she can never be mine!

And how could I resist slipping ‘A Smuggler’s Song’ into That Burning Summer? ( ‘All Marsh folk has been smugglers since time everlastin’ says Tom Shoesmith – or Puck. ‘Twould be in her blood to listen out o’ nights.’)

As a child I never made the connection between these smugglers and the Owlers I read about in the works of another author I devoured at the time: Monica Edwards. (The White Riders was a particular favourite). It was thanks to Monica Edwards that I knew all Lookers and sheepshearing and fishing for eels on the Marsh. I also had no idea that one of my all-time-favourite-authors E.Nesbit was buried on the Marsh.

As a child I never made the connection between these smugglers and the Owlers I read about in the works of another author I devoured at the time: Monica Edwards. (The White Riders was a particular favourite). It was thanks to Monica Edwards that I knew all Lookers and sheepshearing and fishing for eels on the Marsh. I also had no idea that one of my all-time-favourite-authors E.Nesbit was buried on the Marsh.

I’ve always loved plots of concealment – the idea of a child hiding a stranger who could be either friend or foe. Here my early influences are Bette Greene’s The Summer of my German Soldier (1973) and Barbara Leonie Picard’s The Young Pretenders (written in 1971, set in 1745). Mary Treadgold’s We Couldn’t Leave Dinah (Channel Island occupation, a cave hideaway, spies and ponies to boot), Noel Streatfeild’s When the Siren Wailed and Nina Bawden’s Carrie’s War are all buried deep in my psyche too, along with The Other Way Round.

(Channel Island occupation, a cave hideaway, spies and ponies to boot), Noel Streatfeild’s When the Siren Wailed and Nina Bawden’s Carrie’s War are all buried deep in my psyche too, along with The Other Way Round.

(And here I confess to having become a blushing wreck as I declared my love to Judith Kerr at Tales on Moon Lane earlier this summer.)

And finally, as I realised when I watched the incredible production of Othello at the National last month, this was the play which long ago established a model for falling in love that has never left me:

‘She loved me for the dangers I had pass’d,

And I loved her that she did pity them.’

When you’ve read That Burning Summer, you’ll understand.

Links for the Kipling Society and the Monica Edwards Appreciation Society.

Category News | Tags: Bette Greene, book genes, Brookland, Dymchurch, Kipling, literary inspiration, Monica Edwards, Rewards and Fairies, Romney Marsh, That Burning Summer, We Couldn't Leave Dinah

Leave a Reply