Their fight, our fight?

1November 21, 2012 by Lydia Syson

When I made the decision to write A World Between Us entirely from the perspectives of the three main characters, interweaving the close third-person narratives of Felix, Nat and George, it solved some problems and created others. The chaos of war, combined with the effects of propaganda and censorship, made it extraordinarily hard for an individual to see the big picture. I needed to reflect this fact, without losing sight of the longer view myself. Then there’s the conundrum nearly all writers of historical fiction come up against: how do you deal with attitudes expressed by characters which were commonly held at the time a book is set, but are now, thankfully, considered unacceptable?

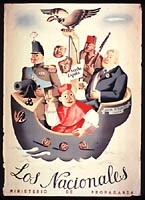

Nat’s first encounter with the Army of Africa at the Battle of Jarama made me think hard about this. In fact I can’t stop thinking about the Moroccans who fought for Franco during the Spanish Civil War, thousands of whom lie in unmarked graves in Spain. I wrote briefly last month about hidden histories. An African perspective on the events of 1936-39 is still in the process of being uncovered; I’ve just started reading Sebastian Balfour’s fascinating book on the subject, Deadly Embrace (O.U.P., 2002). To the British International Brigaders at the time however, Moroccan soldiers in the Army of Africa were simply called ‘Moors’. The very word induced terror, partly due to ancient prejudices, partly because of the particularly brutal methods of combat in which they had been trained, and the way in which the Nationalists deliberately rewarded their victories with permission to loot indiscriminately.

me think hard about this. In fact I can’t stop thinking about the Moroccans who fought for Franco during the Spanish Civil War, thousands of whom lie in unmarked graves in Spain. I wrote briefly last month about hidden histories. An African perspective on the events of 1936-39 is still in the process of being uncovered; I’ve just started reading Sebastian Balfour’s fascinating book on the subject, Deadly Embrace (O.U.P., 2002). To the British International Brigaders at the time however, Moroccan soldiers in the Army of Africa were simply called ‘Moors’. The very word induced terror, partly due to ancient prejudices, partly because of the particularly brutal methods of combat in which they had been trained, and the way in which the Nationalists deliberately rewarded their victories with permission to loot indiscriminately.

My struggles to write a succinct yet nuanced glossary of ‘Moorish scream’ for the multitouch iBook edition of A World Between Us – made easier thanks to the help of Jessamy Harvey, who recommended Balfour’s book – brought home to me the huge gulf between non-Spanish combatants in that war. A young working-class Jewish East Ender like Nat, mid-battle on an exposed hillside, witnessing the slaughter of his comrades and facing imminent death himself at the hands of the Regulares, would hardly have had the time, knowledge or inclination at that moment to consider the extraordinary complexity of the thousand-year history of the ‘Moors’ on the Iberian peninsula.

Oliver Law was the first black man to command an integrated American military unit. He was killed at the Battle of Jarama after leading the Abraham Lincoln Brigade for only four days.

Non-combatant volunteers and journalists had a little more time to reflect, perhaps. Here’s Reg Saxton in an interview recorded for the Imperial War Museum, remembering a Moroccan soldier who had been shot in the leg and was stuck for five days before the Republicans picked him up:

‘…he was starving – a wizened little chap with this horrible septic leg – and we asked how long he’d been in the mountains. I can almost hear his rather squeaky voice: ‘cinco dias, cinco dias’. Anyway he came in and the leg was crawling with maggots – this wound…[had been] exposed to flies in the mountains. In the end the Spanish surgeon amputated his leg. He was hardly fit to stand an amputation, but we couldn’t do anything… and of course he’d been brought in on a stretcher and there were maggots all over the floor. Oh it was filthy. After the operation he was weaker still. The anarchists came and cross-examined him quite severely.’

A wounded Moor is the subject of one of a number of poems written by the black American poet Langston Hughes during the six months he spent in Spain, reporting for the Baltimore Afro-American newspaper.  The poem takes the form of a letter home written by an African-American soldier, and was printed in the Volunteer for Liberty, the English language magazine of the International Brigades, in November 1937. Rather like Canute Frankson in his letter home, Langston Hughes makes strong connections between the two soldiers, in terms of politics, race and humanity, yet in the end he cannot help but acknowledge the distance between them.

The poem takes the form of a letter home written by an African-American soldier, and was printed in the Volunteer for Liberty, the English language magazine of the International Brigades, in November 1937. Rather like Canute Frankson in his letter home, Langston Hughes makes strong connections between the two soldiers, in terms of politics, race and humanity, yet in the end he cannot help but acknowledge the distance between them.

Letter from Spain – Langston Hughes

Lincoln Battalion,

International Brigades,

November Something, 1937

Dear brother at home:

We captured a wounded Moor today.

He was just as dark as me.

I said, Boy, what you been doin’ here

Fightin’ against the free?

He answered something in a language

I couldn’t understand.

But somebody told me he was sayin’

They nabbed him in his land

And made him join the fascist army

And come across to Spain.

And he said he had a feelin’

He’d never get back home again.

He said he had a feelin’

This whole thing wasn’t right.

He said he didn’t know

The folks he had to fight.

And as he lay there dying

In a village we had taken,

I looked across to Africa

And seed foundations shakin’.

Cause if a free Spain wins this war,

The colonies, too, are free –

Then something wonderful’ll happen

To them Moors as dark as me.

I said, I guess that’s why old England

And I reckon Italy, too,

Is afraid to let a workers’ Spain

Be too good to me and you –

Cause they got slaves in Africa –

And they don’t want ’em to be free.

Listen, Moorish prisoner, hell!

Here, shake hands with me!

I knelt down there beside him,

And I took his hand –

But the wounded Moor was dyin’

And he didn’t understand.

Salud,

Johnny

It strikes me that this poem wrestles with questions that are at the core of creating character and telling stories, particularly when it comes to historical fiction, just as they are at the heart of political solidarity. At what point does identification become over-identification? How do you know where to draw the line when it comes to making the voiceless speak?

Category News | Tags: Abraham Lincoln, Army of Africa, Black History, Langston Hughes, Moors, Moroccans, Oliver Law, prejudice, Reg Saxton, Regulares, solidarity

Great blog post Lydia – giving a voice to the forgotten must be one of most rewarding (yet difficult) parts of writing.