Island of Last Hope

0November 25, 2013 by Lydia Syson

A group of Polish fighter pilots walking away from a Hawker Hurricane in October 1940, probably at RAF Northolt in West London. They were apparently photographed after a sortie – one of over a thousand made in the first six months alone of Squadron 303’s formation. The expressions on these young men’s faces are mixed – relief, uncertainty, perhaps even surprise and joy that they are actually still alive.

There’s a myth that the Polish Air Force was destroyed on the ground within days of Hitler’s invasion of Poland on 1st September 1939. In fact, despite their outnumbered and out-of-date planes, Poland’s highly trained pilots fought bravely for several weeks before accepting defeat. By 17th September, the country ‘first to fight’ had been invaded by Russia from the East, and would soon be doubly occupied. But for the pilots the battle was far from over.

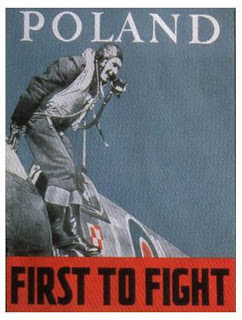

Poster designed in 1942 by Marek Żuławski, a Polish expressionist painter and graphic artist who settled in London in 1936.

Descriptions of their departure from Poland make heartbreaking reading. Adam Zamoyski, author of The Forgotten Few: The Polish Air Force in World War II, reckons that about 80% of the PAF survived the first Blitzkrieg of World War Two and managed to escape capture. 9,276 crossed the border into Rumania (not all as easily as Henryk in That Burning Summer), 900 fled to Hungary, about 1,000 escaped via the Baltic states of Lithuania or Latvia, and another 1,500 were captured by the Soviets and sent straight to labour camps. The aim was to regroup in France.

By late December, 1939, Michal Leszkiewicz, a future Bomber Command pilot who had escaped from Poland via Rumania at the age of 23, was sailing along Asia’s shoreline. He recorded in his diary: ‘We’re probably sailing to Syria. A vague fear of the unknown – a purely human instinct. When you know what to expect, you don’t go to pieces. We have to – we must go on. The responsibility lies with us, the young people; they’re turning to us even in Poland – the innocent ones whom fate has wronged . . .we are their hope.’

Despite his great love and commitment to his homeland, Michal Leszkiewicz never again returned to Poland, and died in England in 1992. His diary made a huge impression on me when I was finding out about the extraordinary odysseys so many airmen made before they reached Britain. I drew on his account for my descriptions of Henryk’s sea voyage from Bulgaria to Beirut, his arrival in the Middle East, the journey to France, and his frustration at the chaos there. On arrival, he found himself interned in miserable conditions in France with refugees from the defeated Spanish Republic.

By June 1940, France too had fallen. The remaining Polish airmen were evacuated to Britain. Arriving exhausted and battleweary in the only allied country left unoccupied in Western Europe, they called it ‘The Island of Last Hope’. On 18th June, Churchill famously declared: ‘Hitler knows that he will have to break us in this island or lose the war. If we can stand up to him, all Europe may be freed and the life of the world may move forward into broad, sunlit uplands.’ J.B.Priestley (‘That Yorkshire man on the radio – the one with the calming voice Aunt Myra loved to listen to’ TBS, p. 100) remembered the Germany he’d known and loved before the last war, and warned ‘any country that allows itself to be dominated by the Nazis will not only have the German Gestapo crawling everywhere, but will also find itself in the power of all of its own most unpleasant types – the very people who, for years, have been rotten with unsatisfied vanity, gnawing envy, and haunted by dreams of cruel power. Let the Nazis in, and you will find that the laziest loudmouth in the workshop has suddenly been given the power to kick you up and down the street, and that if you try to make any appeal, you have to do it to the one man in the district whose every word and look you’d always distrusted.’

The forty Polish pilots who took to the skies at the beginning of the Battle of Britain were scattered at first among a number of RAF squadrons. Most were among the 2,000 or so airmen who’d been kicking their heels in Britain for months already. When the earliest pilots first arrived, between December 1939 and February 1940, they were given a frustratingly slow induction into RAF life, involving English lessons, education in the King’s Regulations, and endless parades and rollcalls: it seemed they would never be allowed near an actual plane.

This poster promoting Anglo-Polish unity is based on an original photo of pilot Bogdan Jan Witold Muth of 302 Sqn (1918-1998). Many thanks to Kelvin Youngs of Aircrew Remembered for this information.

Zamoyski’s account of the clash of military cultures between British and Polish pilots makes fascinating reading. The Poles were driven to distraction by British officers – ‘ostriches’, they called them – who seemed to be hiding their heads in the sand about the real nature of the threat from Germany. The British, meanwhile, were disconcerted to say the least by the newcomers’ manners:

‘The Polish habit of saluting everyone, on station, in town, in restaurants, irritated the British officers, who found that they could not cross the airfield or walk down a street without acknowledging several dozen salutes. “They were always giving you salutes even if it was their despatcher handing you a cup of coffee,” recalls an RAF officer. “The heel-clicking that went on was terrific,” remembers one RAF fitter, “and they had a funny way of bowing stiffly, from the waist up, like tin soldiers.”‘

Despite this, the Poles did not take easily to the kind of hierarchical deference traditional in the British military. Group Captain A.P.Davidson, a former air attaché in Warsaw and the station commander at RAF Eastchurch, near Sheerness, where the first Polish airmen were based, was shocked and baffled by their attitudes:

“Whilst on the one hand there exists a distinct class feeling between officers and airmen and the former often treat the latter with a lack of consideration unknown in our own Service, on the other hand, officers fraternise with airmen, walk about and play cards with them.”

Morale improved once the Poles were finally allowed to fly, but then they discovered that everything on a British aircraft was back-to-front, so all their reflexes had to be reversed. You had to push instead of pull to open the throttle, and even the toggle for opening the parachute was on the ‘wrong’ side. There was also the difficulty of judging in feet and miles, not metres and kilometres, and new navigational aids to master like radar (only just adopted, and still secret) and radios. The British tactic of close formation flying seemed suicidal to the experienced Poles, for pilots had to pay far more attention to not colliding with each other than looking out for attacking aircraft. Four tight ranks of three planes were supposedly protected by the middle plane of the last rank, known as the ‘weaver’, but 32 Squadron, based at Biggin Hill, lost 21 of these pilots in three weeks, each ‘picked off’ by the enemy without the rest of the squadron even noticing.

A myth that came to dominate war films and popular memory was that all Polish pilots were reckless and individualistic. The stereotype arose partly because they were trained to fire at much closer range than British pilots – almost at pointblank. (‘Those crazy Poles’, thinks Peggy,That Burning Summer, p. 43). This scene from the 1969 film The Battle of Britain (whose uncountable stars included Laurence Oliver as Hugh Dowding and Trevor Howard as Keith Park) is typical of British attitudes:

(Incidentally, and somewhat chillingly, the German aircraft used in this film were provided by Franco’s Spanish Air Force: a mixture of Heinkels, still used for transport, and retired Messerschmitt 109s.)

In August 1940, two new Polish fighter squadrons were formed: No. 302, ‘City of Poznań’, and No. 303, ‘Kościuszko’. By 1941 a fully-fledged Polish Air Force was operating alongside the RAF. By the end of the war, Polish pilots had won 342 British gallantry awards, and 303 Squadron claimed the highest number of kills of all the Allied squadrons in the Battle of Britain yet its death rate was the lowest.

A view today of Walland Marsh, part of Romney Marsh, nr Scotney, Lydd, Kent, an area under sea till about 600 and only populated during the 12th and 13th centuries.

On 11th September 1940 at 16.15 hrs, Sergeant Stanisław Duszyński was shot down over Romney Marsh, not far from Lydd, while attacking a Ju 88. He was 24, and like Henryk in That Burning Summer, he both trained at Deblin and had initially been evacuated to Rumania in 1939, later travelling to France. Neither his body nor his Hurricane were recovered during the war, although unsuccessful efforts, both official and unofficial, were made in 1973 and 1996. The heartbreaking photographs below belonged to his fiancé, Czesława (below), and were kindly sent to me by her granddaughter, Aggie, who said that although her grandmother went on to marry and have children, she was never the same again after Stanisław’s death. On this photograph, just below his silver eagle flying badge (gapa), you can see the handwritten words ‘Kocham Cie zawsze’, which mean ‘I will love you always’. Many thanks to the Wyszynski family for permission to publish these pictures here.

Six months after Duszyński’s disappearance, Pilot Officer Bogusław Mierzwa’s Spitfire came down in flames on the stony promontory of Dungeness, not far from the lighthouse. Another pilot of the 303 Squadron, Mieczyslaw Waskiewicz, crashed into the sea off the point and was never found. Both were returning from a mission to escort six Blenheims sent to bomb a fighter airfield in France. Mierzwa had been awarded his Pilot’s Wings in Poland less than two years earlier, at the age of 22, not three months before the invasion of Poland. Until recently, this tattered Polish flag still flew over the spot where his aircraft burned, but there is now a more substantial memorial which tells their stories.

Altogether, between 1939 and 1945, well over 200,000 Poles fought in all the forces under British High Command. But for complex reasons, by 1946, anti-Polish sentiment in Britain had become so bad that ‘Poles go Home’ graffiti had begun to appear near Polish Air Force bases. Squadron 318 Spitfire pilot Stefan Knapp, a sculptor and painter who suffered from recurring nightmares and insomnia for years after the war, recalled the change in his memoir, The Square Sun (1956):

‘I was choking with the bitterness of it…Not so long ago I had enjoyed the exaggerated prestige of a fighter pilot and the hysterical adulation that surrounded him. Suddenly I turned into the slag everybody wanted to be rid of, a thing useless, burdensome, even noxious. It was very hard to bear.’

In the programme for the Allied Victory  Celebrations in London a year later, you will only find a mention of Poland under one heading – the Central Band of the Royal Air Force. By this time it was Stalin, not Hitler, who seemed to require appeasement. The terrible fate of Poland, a subject too vast to tackle here and now, had already been determined around conference tables at Tehran, Yalta and Potsdam.

Celebrations in London a year later, you will only find a mention of Poland under one heading – the Central Band of the Royal Air Force. By this time it was Stalin, not Hitler, who seemed to require appeasement. The terrible fate of Poland, a subject too vast to tackle here and now, had already been determined around conference tables at Tehran, Yalta and Potsdam.

Find out more:

Adam Zamoyski, The Forgotten Few: The Polish Air Force in World War II (1995, Pen & Sword Aviation, 2009)

Lynne Olson & Stanley Cloud, For Your Freedom and Ours: The Kosciuszko Squadron – Forgotten Heroes of World War II, (2004)

Robert Gretyngier, in association with Wojtek Matusiak, Poles in Defence of Great Britain, July 1940-June 1941 (London, Grub St, 2001)

Josef Zielnski, Polish Airmen in the Battle of Britain, 2005 (A very useful book, with a short chapter on every airman, but not easy to get hold of)

Kenneth K. Koskodan No Greater Ally: The Untold Story of Poland’s Forces in World War II (Osprey, 2011)

Arkady Fiedler, 303 Squadron: The Legendary Battle of Britain Fighter Squadron (2010)

F.B.Czarmomski, They Fight for Poland: The War in the First Person, (1941 – Front Line Library)

Patrick Bishop, Fighter Boys: Saving Britain 1940, (Harper, 2003)

Jonathan Falconer, Life as a Battle of Britain Pilot, (The History Press, 2007)

Battle of Britain monument…find out about the Polish airmen.

RAF Museum online exhibition on Polish Pilots

Polish Institute and Sikorski Museum

Commemorative site with information to help find all the cemetaries in the world where Polish airmen were buried during WW2

Aircrew Remembered remembers and honours ‘everyone involved in aviation from all nations and all eras’

Battle of Britain heritage trail

Further background reading and links for That Burning Summer can be found here. You can buy a ‘For Freedom’ T-shirt commemorating all the Polish aircrew killed in the Battle of Britain from Philosophy Football.

Identification of pilots in first photograph, left to right, in the front row: Pilot Officer Mirosław Ferić, Flight Lieutenant John A Kent (Commander of ‘A’ Flight – Kent wrote out phonetically on his trouser leg the Polish words for every procedure involved in take-off, flying and landing), Flying Officer Bogdan Grzeszczak, Pilot Officer Jerzy Radomski, Pilot Officer Witold Łokuciewski, Pilot Officer Bogusław Mierzwa (obscured by Łokuciewski), Flying Officer Zdzisław Henneberg, Sergeant Jan Rogowski and Sergeant Eugeniusz Szaposznikow. In the centre, to the rear of this group, wearing helmet and goggles is the infamous F.O. Jan Zumbach.

Category News | Tags: 303 squadron, anti-Polish racism, attacks on Poles, Bogusław Mierzwa, City of Poznań, First to Fight, heel-clicking, Island of Last Hope, J B Priestley, Kościuszko, Michal Lesziewicz, Polish Air Force, Polish pilots, Rumania, Stanisław Duszyński, That Burning Summer, WW2 myths

Leave a Reply