Wartime Christmas

0December 22, 2013 by Lydia Syson

Today’s war-themed window in the Carnegie 2014 Advent Calendar by We Sat Down is my inspiration for this final post of the year. Christmas in wartime tends to be peculiarly poignant – so often dark with separation, and haunted by the ghosts of past celebrations. Ritual is disrupted, and hope can seem fragile. Both That Burning Summer and A World Between Us include not scenes, but memories of Christmas.

Confused and ill, hiding in an isolated church in Kent, Henryk half-believes himself back in Beirut. In 1939 a number of Polish airmen spent their first Christmas away from home trapped on the boat that had brought them from Bulgaria, unable to embark:

Nothing to eat for hours and hours, nothing to do but sing, and drink. Someone had a mouth organ. Zygi. Yes, that’s right, it was Zygi who played the mouth organ, really quite well, considering. Where was Zygi now? He played tangos and then the Funeral March. And of course Boże, coś Polskę. Polskę, Polskę ah Polskę. Home in their hearts and head.

But nobody could actually speak of home. They wept. They drank some more. Such longing. Henryk felt it again now. He swallowed the spit pooling in his mouth, and remembered thinking of the girls as they walked around the Christmas tree in their best dresses, just as they had the year before and the year before that. Every year the same. Could it possibly be true again? He didn’t know then, not in Beirut. He could still believe it was possible.

(That Burning Summer, p. 145)

The idea of Christmas plays a very different role in A World Between Us. Re-united with Nat at last, drinking sherry in a bar in besieged Madrid, Felix is reminded of Christmas at home, and what she’s missed. Christmas is a measurement of how far she’s come.

‘”Makes you homesick, does it?” Nat was sympathetic.

“The opposite…It makes me realise what I’ve escaped. The annual sherry ritual. So predictable. So irritating. So much fuss about nothing. Ghastly. In fact, I don’t even know why I’m talking about it. Of all things…”

“I want to hear.” He leaned forward.

“Oh, don’t get the wrong idea. It’s not a proper ritual, not religious or anything. It’s just that’s when we always drink it. On Christmas Day, once a year. The sherry bottle comes out of the corner cupboard, after church and before lunch. Harvey’s Bristol Cream. It’s funny how it never seems to run out.”

Six cut-glass sherry glasses, polished so carefully by her pedantic and controlling older brother, assume a weight of significance which Nat finds hard to understand. ‘”I don’t know why I thought of it,”‘ says Felix, eventually. ‘”I suppose because it all seems so irrelevant now. All that worrying about things.”‘ (A World Between Us, pp130-132)

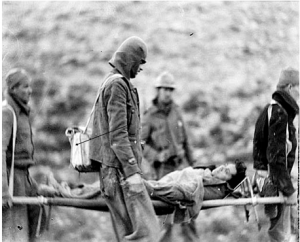

During the Spanish Civil War, the most memorable Christmas for many International Brigaders was in 1937. It was the year the Republicans ‘got’ Teruel for Christmas, briefly recovering the town from Nationalist forces in the middle of the worst winter Spain had seen for twenty years. “Teruel is Christmas present enough,” wrote the American poet and ambulance driver James Neugass, author of the most vivid and moving memoir of the Spanish Civil War I have ever read, War is Beautiful.

Here is Neugass’ description of Christmas morning at Alcorisa:

The radio in the ward . . . purrs peace across the Western hemisphere. Organ music from half the great cathedrals of Europe rolls over the coughing figures on the beds. I am very glad for the cold which seems to have permanently crippled my sense of smell. From Finland to Greece, Church dignitaries, ministers of Education, senators and cabinet ministers sob their two cents’ worth of heavenly peace over the air, with the piety of whores on a holiday.

Nevertheless, that stained-glass purplish Christmas feeling is inescapable. It is difficult not to feel sorry for yourself. All of the world is calm and pure on December 25th.

The dance last night at Andorra was no riot. I cannot boast of a hangover. The medical alcohol ran short.

That afternoon, the ward was visited by Len Crome (probably now a familiar name to readers of this blog):

Commandante Crome (real nom de guerre)…has just addressed us. C. is the son of White Russians, educated in Scotland. His riding boots are the only perfectly polished leather I have seen in Spain. Some of us think that C. is a Prince or a Duke. He could step into the leading role of a Hollywood Zenda romance. Why has he come to Spain?

The speech Neugass recalls gives a good taste of Crome’s style of leadership.

“You must remember that the infantry think as much of the Medical Corps as they do of their helmet. You are their shield. You must also remember that each of you is personally responsible to the anti-fascist men and women of the world who sent you here. They are your commanders. We officers are here to organise rather than to command. With the discipline you shall impose on yourselves, we shall win.

“Are there questions?”

(War is Beautiful, pp 78-81)

Category News | Tags: 2014 Carnegie Advent, A WORLD BETWEEN US, Beirut, Christmas, Len Crome, Neugass, sherry, War is Beautiful, wartime, We Sat Down

Leave a Reply