Come and see the blood in the streets

0April 22, 2013 by Lydia Syson

What prompted thousands of men and women, some only teenagers (like Nat and Felix in A World Between Us), to leave everything they knew to go and help the Republican cause in Spain – often without a word to their families? Many had never left Britain before, most didn’t speak a word of Spanish, and a fifth of them were killed there.

What prompted thousands of men and women, some only teenagers (like Nat and Felix in A World Between Us), to leave everything they knew to go and help the Republican cause in Spain – often without a word to their families? Many had never left Britain before, most didn’t speak a word of Spanish, and a fifth of them were killed there.

In Ken Loach’s Land and Freedom, a documentary film at a political meeting is the deciding factor for the idealistic young volunteer David Carr. Earlier this month, as I watched Ivor Montagu’s astonishingly vivid documentary The Defence of Madrid earlier at a rare screening organised by the London Socialist Film Co-op at the Renoir cinema, I wondered whether the clips in Loach’s film might have come from Montagu’s. I’ve just checked and they didn’t – Land and Freedom is, after all, subtitled ‘A story from the Spanish Revolution’ and quite rightly the archive footage used in it was clearly filmed in Barcelona.

My curiosity about this was pricked by the lively discussion which followed this screening (which was followed by Will the real terrorist please stand up?, a documentary on the relationship between the USA and Cuba). The first speaker from the audience criticised The Defence of Madrid for its lack of revolutionary zeal (demonstrating a point made in my recent post on Homage to Catalonia about the relentless persistence of the idea that Franco won the war because of divisions on the left rather than the combined might of the Italian/German fascist war machine and the Non-Intervention policy spearheaded by Britain.) Jim Jump of the International Brigade Memorial Trust gently pointed out how very different the situations in Barcelona and Madrid were in late 1936 when Montagu went to make the film.

The Spanish capital was then at the start of what became a three-year-long siege by Nationalist forces. General Mola had just coined the term ‘fifth column’, declaring that while four columns of Nationalist soldiers were all too visibly approaching the capital, a ‘fifth’, made up of right-wing sympathisers within the city, was secretly making plans to ensure the invasion was effective. The shock for British audiences of seeing what was actually happening in the Spanish capital must have been intense. Now that we are so horribly used to seeing images showing the effects of aerial bombardment on cities and towns, it’s hard to appreciate the impact news of the war in Spain had around the world. It was the first in Europe in which more civilians than combatants were killed. Last year, when I was interviewing a woman now in her late 80s about her memories of the second world war on Romney Marsh, she told me how horrified she had been as a child to see newsreels of Spanish bombing, and that she remembered turning to her mother in the cinema to say: “It couldn’t happen here, could it?”

The kind of scenes shown in Montagu’s film are considerably more detailed than any  newreel, and of course they did indeed soon become familiar in Britain too. You see houses ripped apart to reveal torn wallpaper, flapping curtains and fireplaces hanging several stories up; people buried under rubble; sandbags in the street; dead children in numbered rows. People look up at the blurred planes crossing the skies above and ask, ‘Are they ours?’, a question echoed in the opening paragraphs of A World Between Us. In a hospital, a wounded Moroccan solider refuses food because he’s been told by his Nationalist masters that the Republicans will try to poison him.

newreel, and of course they did indeed soon become familiar in Britain too. You see houses ripped apart to reveal torn wallpaper, flapping curtains and fireplaces hanging several stories up; people buried under rubble; sandbags in the street; dead children in numbered rows. People look up at the blurred planes crossing the skies above and ask, ‘Are they ours?’, a question echoed in the opening paragraphs of A World Between Us. In a hospital, a wounded Moroccan solider refuses food because he’s been told by his Nationalist masters that the Republicans will try to poison him.

The film is impressionistic and urgent, clearly made in a hurry, under pressure. It has none of the polish of the exquisitely crafted Ministry of Information propaganda films made by Humphrey Jennings to bolster morale on the British Home Front in the early 1940s. The Defence of Madrid is strikingly non-polemical. This is what’s happening, it simply seems to say. What are you going to do about it?

In the audience at the Renoir was Hetty Bower, whom I first met at my grandfather’s funeral, when she told me that she thought his death made her the last surviving member of the Independent Labour Party’s Revolutionary Policy Committee. As she explained at the screening, she knew Ivor Montagu when she was working for Kino Films, the progressive film distribution and production company responsible for arranging screenings of The Defence of Madrid, which was shown at Trade Union and political meetings up and down the country to raise funds for the Brigades and for Medical Aid for Spain, and to draw attention to the urgency of the cause. Typical audiences were women’s co-operative groups and Labour and Communist Party branches. The Edmonton Labour Party raised £72 at one screening, the Rochdale Clarion Cycling Club £38, said BFI curator Ros Cranston, introducing the film.

In the audience at the Renoir was Hetty Bower, whom I first met at my grandfather’s funeral, when she told me that she thought his death made her the last surviving member of the Independent Labour Party’s Revolutionary Policy Committee. As she explained at the screening, she knew Ivor Montagu when she was working for Kino Films, the progressive film distribution and production company responsible for arranging screenings of The Defence of Madrid, which was shown at Trade Union and political meetings up and down the country to raise funds for the Brigades and for Medical Aid for Spain, and to draw attention to the urgency of the cause. Typical audiences were women’s co-operative groups and Labour and Communist Party branches. The Edmonton Labour Party raised £72 at one screening, the Rochdale Clarion Cycling Club £38, said BFI curator Ros Cranston, introducing the film.

Ivor Montagu, who also edited and produced films with Hitchcock, was responsible  for some of the most significant films to be made on the left in the 1930s. The Progressive Film Institute, which he founded, subsequently made four more films about the Spanish Civil War: News from Spain (1937), Crime Against Madrid (1937), Spanish ABC (1938) and Modern Orphans of the Storm (1937). ‘We did what we could’, Montagu said in later life, ‘but it was not enough.’ A circular from the Relief Committee for the Victims of Fascism, which commissioned The Defence of Madrid, announced that this ‘great film’ would be shown twice nightly, December 28th-29th, and that ‘in addition to the Film, the Spanish Situation will be dealt with by the following Speakers: D.N.Pritt, Isabel Brown, Leah Manning, Ivor Montagu’ one of whom was promised to appear at all four screenings. 1000 tickets were issued for each show, at sixpence each.

for some of the most significant films to be made on the left in the 1930s. The Progressive Film Institute, which he founded, subsequently made four more films about the Spanish Civil War: News from Spain (1937), Crime Against Madrid (1937), Spanish ABC (1938) and Modern Orphans of the Storm (1937). ‘We did what we could’, Montagu said in later life, ‘but it was not enough.’ A circular from the Relief Committee for the Victims of Fascism, which commissioned The Defence of Madrid, announced that this ‘great film’ would be shown twice nightly, December 28th-29th, and that ‘in addition to the Film, the Spanish Situation will be dealt with by the following Speakers: D.N.Pritt, Isabel Brown, Leah Manning, Ivor Montagu’ one of whom was promised to appear at all four screenings. 1000 tickets were issued for each show, at sixpence each.

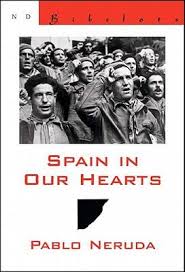

Films like this were clearly life-changing for some who saw them. Even more so was the effect of living through this period in Madrid, as the Chilean poet Pablo Neruda did. As Jim Jump reminded us, it produced Neruda’s poem ‘Let me explain a few things’, recited by Harold Pinter in his 2005 Nobel lecture because he believed it to be the most ‘powerful visceral description of the bombing of civilians’ in contemporary poetry.

And you will ask: why doesn’t his poetry speak of dreams and leaves

and the great volcanoes of his native land?

Come and see the blood in the streets.

Come and see

the blood in the streets.

Come and see the blood

in the streets!

(The Defence of Madrid is in the BFI National Archive. You’ll find a list of all BFI Spanish Civil War holdings here. The letter quoted comes from the University of Warwick Library’s magnificent resource, Trabajadores – learn more about this amazing archive at History Workshop Online. Find out more about the context of The Defence of Madrid in Ian Aitken’s book Film and reform: John Grierson and the Documentary Film Movement, 1990)

Category News | Tags: Anti-fascism, blood on the streets, fundraising documentary, Ian Hart, International Brigade Memorial Trust, Ivor Montagu, Jim Jump, Ken Loach, Land and Freedom, London Socialist Film Co-op, Medical Aid for Spain, Propaganda films, Spanish Civil War films, The Defence of Madrid, Trabadajores, Trabajadores

Leave a Reply